Tell Cornell's Peggy Walbridge that she is Cornell's greatest woman fencer and she's quick to disagree. "No I'm not. Grace Acel was. She was phenomenal." Indeed, Acel's accomplishments are impressive, with two national fencing championships in 1942-43. Cornell had an even earlier repeat women's national fencing champion, Elizabeth Ross, in 1930-31. Karen Denton also reigned as national champion in 1968.

Tell Cornell's Peggy Walbridge that she is Cornell's greatest woman fencer and she's quick to disagree. "No I'm not. Grace Acel was. She was phenomenal." Indeed, Acel's accomplishments are impressive, with two national fencing championships in 1942-43. Cornell had an even earlier repeat women's national fencing champion, Elizabeth Ross, in 1930-31. Karen Denton also reigned as national champion in 1968."In the 1960s Cornell had a very good team," explains Walbridge. "[Michel] Sebastiani (the recently-retired Princeton coach, then Cornell's coach) was responsible for making Cornell's teams so strong."

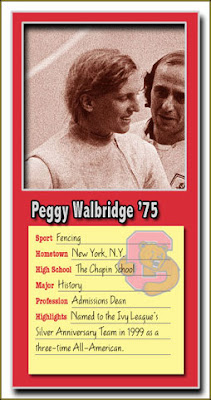

Walbridge benefited from the growing strength of Cornell's program, for she did not fence competitively in high school. "I went to an all-girls school," she remembers, "and played on any and every team that I could get on." But there was no fencing team, and Walbridge chose Cornell "because it would be the biggest challenge for me personally, and it had a very strong liberal arts college." Fencing was not a factor.

Her initiation to Cornell fencing was inauspicious. "I was horrible, laughable freshman year, won very few bouts," she says. But by sophomore year Walbridge, and her team, hit its stride. "Our team flattened just about everyone we fenced," she says. "We won every team match our sophomore to senior seasons, by scored of 15-1, 16-0. The least we won was by 12-4." The Cornell women's fencing team won the 1972-73 national championships, and barely lost the 1974 title.

For Stephen Eschenbach's full story, please visit Ivy@50.